GeoLegal Weekly #5: A2J = Access to Jerks?

I provoke about access to justice, inspired by an egregious case of lawyers acting badly; also, a tell-all about the international arbitration apparatus and some nice press about Hence and insurance.

I’ve spent a lot of the last year digging into access to justice (A2J) issues in the US and abroad. While other countries enable access to legal robots, the US seems pretty good at enabling access to jerks. And by that I mean predatory human lawyers.

OK, I’ve invited a ton of private practice lawyers onto this list and I do not think you are jerks. You take your client responsibilities seriously and act to protect and execute the fundamental rights of your clients. You do pro bono work and hold yourself to a very high ethical standard in your practice. But not all lawyers are like you. And it is currently much easier to access legal services from highly deceptional practitioners than it is to access technology to support representing oneself in court or, often, than to access the dwindling supply of accomplished, effective and ethical legal aid attorneys.

What’s gotten me so worked up? A recent expose on a debt settlement company with ties to the “Wolf of Wall Street,” that managed a network of law firms engaged in allegedly taking serious advantage of customers with large amounts of debt.

The most interesting part of the story is not that the company, Strategic Financial Solutions, once had the current Governor of New York at a ribbon cutting ceremony. Or that it executed an employee buyout at a valuation of over $200mn - which is likely now worth zero.

No, the most interesting piece part of the piece was the debt settlement company’s relationship with law firms. The New York Times reported that “Strategic relies on a network of at least 20 law firms, which take on an average of 5,000 to 10,000 clients each - extremely high loads for firms that had five to 20 employees.” One of these law firms was purchased for $10 by a newly minted lawyer who would later have his license suspended for unauthorized practice of law and fee sharing with non-attorneys, among other reasons. While operating, that law firm and others allegedly were law firms in name only, with customer interactions routed to non-attorneys and with mobile notaries posing as paralegals or lawyers when it came time for documents to be signed. While Strategic maintains that real lawyers signed off on all settlements, many customers documented a failure of their lawyers to ever show up in court - which isn’t a surprise at the scale they were operating.

OK, so, there are bad apples everywhere and this is a particularly egregious case. But what’s so interesting to me about it is the way that legal fit into the strategy of the purported bad behavior. A prior Florida case against the firm summarized this well: The firm “is masquerading as a law firm to evade various federal and state laws intended to curb deceptive and abusive practices of debt settlement companies…and to project the aura of trustworthiness with a profession that is supervised by the courts and bar organizations.”

My point in running through this is not to show you that I’m good at summarizing New York Times articles but rather that such frauds can continue for years because of:

The unmet need for legal services of those at the bottom half of the economic food chain who are often grasping for solutions to get back above water; and,

The deference of the self-regulatory nature of the legal system to anything registered as a law firm.

Examples like this - law firms effectively controlled by allegedly predatory entities - are held up as reasons not to liberalize the legal sector. I think this case demonstrates the opposite.

This case indicates that the simple fact of being a lawyer or being affiliated with a law firm may afford a regulatory (and marketing) shield not afforded to others. Paraprofessionals at underfunded social good entities and technology solutions that move too close to providing legal advice are much easier to identify and prohibit even if they are much more aligned with the needs of customers than high volume, profit oriented legal work conveyer belts.

This shield often leaves the most in need with only access to, well, jerks.

Where did all the public service lawyers go?

It shouldn’t be a surprise that many would fall for the promise of an “established law firm that specializes in helping clients resolve their own personal debt” at a seemingly affordable price. That’s because there aren’t many other places to turn.

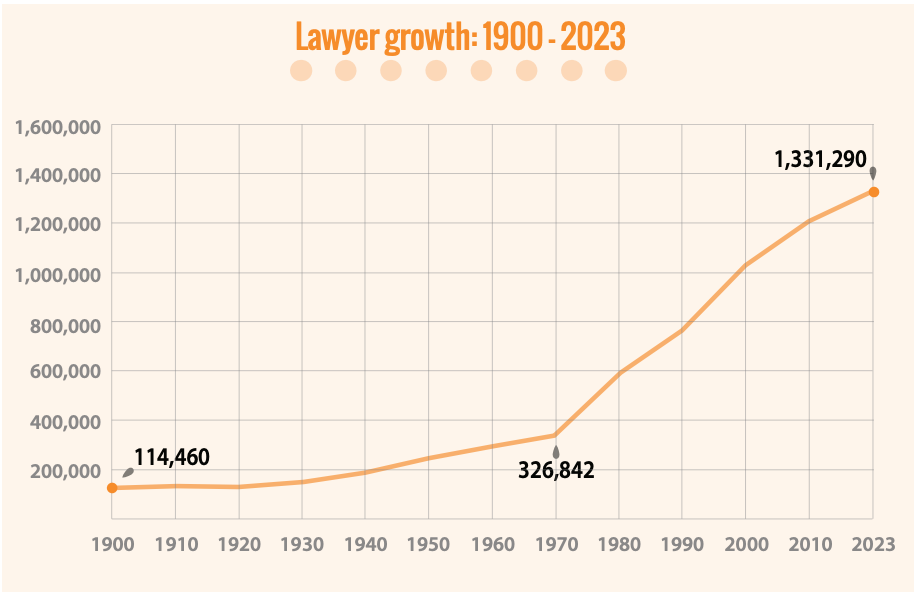

The US has an oversupply of lawyers and it still has a yawning justice gap. This paradox - that there are too many lawyers for the lucrative private jobs available and too few to do legal aid and public service work - is driven by how expensive it is to become a lawyer. Going in debt nearly $200,000 to enter the legal profession triggers down stream professional choices.

There’s also a sense that that’s what legal aid is for - and, indeed, that’s what legal aid is for. But legal aid budgets are stagnating in real terms and have dropped considerably since the 90s as you can see in the chart below of the Legal Services Corporation funding (LSC is a government established independent corporation that is the biggest source of funding for civil legal support for low-income Americans.)

Will technology be the answer?

This isn’t just a story of indebted lawyers deciding not to do public service or government subsidizing it. It’s also a story of innovation - or lack thereof.

One of the biggest factors that is often missed is the massive disparity between how much venture funding goes into legal solutions targeting law firms and corporate legal departments versus what’s being invested in “justice tech” (those solutions improving access to justice.)

Bob Ambrogi over at LawSites has a great piece framing the contrast between LegalWeek (where you and your friends can compete to collect vendor-sponsored Michelin stars) and the Legal Services Corporation’s major tech conference (where you could compete to be first at the cash bar).

In it, he notes that $1.4 billion dollars flowed into legal tech in 2023 (on top of $2.2bn in 2022) - all chasing big firms and corporations. The primary prize for justice tech was the Legal Services Corporation’s Technology Initiative Grants program which gives $5mn in total, with individual recipients generally getting less than $40,000.

Why is this? Bob quotes the old adage that this is because the law firms and big corporate clients are where the money is. That is correct today. For example, if I decided to create a startup designed to automate and manage caseloads of debt collection law firms like those described up top, a venture capital firm could easily understand that the market is big, lucrative and would benefit from technology that could be deployed today. Here comes the check.

But the addressable market in “PeopleLaw” (law for real people problems, not those of corporations) is even more massive. After all, if I created a startup called “George Washington, Esq” because every person in America paid it $1 per year to have access to an AI lawyer, my startup would probably be worth more than the biggest legaltech companies. But I suspect it would be require a much bigger leap of faith.

While there are a lot of questions around what technology can and can’t do, it’s not hard to imagine an AI lawyer today that could deliver more than $1 of value to its users. So if the tech isn’t the issue, what gives?

I think the disparity has to do with the fact that to date big law and big corporate are where you can expect a clear return without requiring regulatory change. George Washington, Esq requires a leap of faith that it would be allowed to practice. And neither the real George Washington nor my AI version could legally practice law today.

This means that the current business models for makers solving PeopleLaw problems are constrained in a way that they are not for tech supporting anyone with a license to practice law. Utah is the only state where technology companies can get waivers of unauthorized practice of law rules, and startups that dare go after the space face threats from state bar associations and class action suits, as I’ve documented for Bloomberg Law here.

In the same Bloomberg piece, however, I outline how I think a focus by big tech on the legal sector is going to ultimately lead to pressure to change all these rules. That’s why we’re starting to see a trickle of VC funding into the PeopleLaw space and I suspect we’ll see a lot more going forward.

One of the best places to see evidence for interest by BigTech in legal is in job postings. Google’s parent, Alphabet, has a company called “X” which is focused on "inventing and launching 'moonshot' technologies that...could someday make the world a radically better place.” Alphabet’s X is currently hiring a "lead for one of our early stage projects focused on applied Large Language Models & generative AI to the legal space."

A moonshot wouldn’t seem necessary for an addressable audience of law firms and corporate legal departments - they already have plenty of software to choose from. No, BigTech sees the opportunity in helping small businesses and regular people engage with the legal sector.

Imagine if I had a legal services co-pilot build into my word processor? Big software companies are imagining that. And big firms are really good at changing the rules in their favor to make things possible.

Could Robots Better Empower Citizens?

To bring this all full circle, we come back to the question of whether the lives of those who engaged with a purportedly nefarious network of law firms ended up better off than they would have had they engaged with AI-based guidance. After all, the customers who wised up about their lawyers in the story above fired them and then tried to negotiate settlements on their own.

I am a strong supporter of liberalizing legal regulations to make space for software to fill the justice gap. There are loads of issues and risks on this pathway, but to me it’s the right pathway. Citizens who don’t have access to their justice system cannot exercise their fundamental rights. In many cases, they cannot be aware of what those rights are without a paid consultation that many cannot afford. Intelligent software will increasingly fills these gaps.

To evaluate this, we should take a look at an AI-based solution. Startup MyPocketLawyer just released a teaser demo of its AI product, which shows how it guides an individual through the process of challenging an employer, receiving a settlement offer, and ultimately identifying an appropriate human lawyer to review it. This is about using AI for much of the process and bringing the lawyer in the loop when necessary. Product demo starts at about 1:30 mark here and below.

While I imagine there are many GPT-based agents that can offer similar advice, this is one that is actively trying to get users comfortable that having their own legal resources is the best place to start. What I find compelling about this approach is that it empowers individuals to engage in more of the legal process on their own than they otherwise would. This makes them less dependent on glossy marketing/telemarketing or on the first registered lawyer or law firm that gets their attention.

By encouraging consumers to think critically about when and how to use lawyers, they will be more likely to avoid predatory actors - and potentially help police the profession against them. They will also cut their legal bills by being able to collaborate with their counsel - using AI to do some basic work, rather than allowing lawyers to capture the full surplus of using AI to do basic work.

As Charlie Hernández, CEO of MyPocketLawyer, tells me:

"We need to recognize that there will never be enough lawyers to solve all the legal problems people face in our country. By positioning consumers and small businesses to address simple legal issues on their own and escalating only the most complex questions to lawyers, we maximize the net benefit for everyone. Consumers see more of their problems solved, small businesses see fewer impediments to growth, attorneys can serve more clients, and we lighten the load on downstream responsive solutions like the court system. If a consumer or small business has a legal issue, they generally have only two choices: pay high hourly fees for a lawyer, or get free but unhelpful (and often inaccurate) information from ChatGPT or a search engine. There is a big gap between those two options, and purpose-built, mission-driven legal technology is perfectly positioned to fill it.

Subsequent posts will dive into how far off this eventuality is, how venture will approach justice tech in the future and other solutions in the space that are particularly unique.

Further Reading

Bill Henderson’s masterful take on turning attention to PeopleLaw: For anyone who has a broader interest in the topics above, I highly recommend you read Bill Henderson’s personal reflection on why he’s devoting more time to PeopleLaw. The post basically argues that Bill’s optimism about the creation of a “one to many” legal sector was premised on an unstated assumption of political stability and economic prosperity - one that readers of my missives will note is an assumption currently being tested by global events. Bill notes that “over multiple generations of lawyers, our legal infrastructure has fallen into appalling disrepair” and that it can only be fixed if we can solve a collective action problem to get people to focus on these issues. In it, he announces a decision to do so himself.

How the government of Nigeria lost $6.6bn in arbitration - and then won it back in court: It’s worth reading about the massive legal battle between Nigeria and an Irish business that took it to international arbitration for billions. Crucially, the story looks at what impact to the entire economy of Nigeria would have been, which is startling. The story is implicitly and explicitly critical of the arbitration industry from multiple angles in a way that I suspect will invite some follow-on stories and additional scrutiny from press and regulators. It’s also a very good read.

—

Finally, I thought I’d include a not so humblebrag about Hence. A few months ago Hence won Zurich Insurance’s Global Innovation Championship out of over 3,000 companies. Sifted covers our development of an attorney recommendation model that we estimate is saving between 2% and 4% of the total cost of claims (not just legal fees.) If you think this is cool, let’s chat.

-SW