GeoLegal Weekly #54: I spread misinformation

As deep-hate met deepfake, I was fooled. Soon it may be you.

First, thanks to everyone who signed up for our soft-launch of Hence Global, our AI-powered news and risk insights software. We can onboard 10 more early adopters this week, so please simply reply if you’re interested.

-

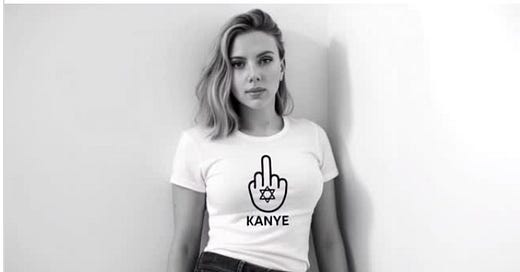

Yesterday, I was multitasking while on a phone call. I was scrolling through my Linked-In feed when a video caught my eye. In the video, a host of Jewish celebrities seemingly fight back against Kanye West’s deplorable swastika Super Bowl publicity stunt. Each is wearing a shirt with a Star of David in the center of a hand giving the finger to the name Kanye. You can watch this deepfake below.

Without thinking hard about it, as I was on a call, I forwarded it to my wife. When I asked her if she saw it, she immediately told me she thought it was fake. Stunned, I realized I had forwarded it before considering whether it was real or not. When I looked closer at it, I quickly saw the hallmarks of a deepfake. At the time, it had not been labeled as such.

In the video, David Schwimmer is featured, coming on the heels of publicly pleading for Elon Musk to de-platform Kanye earlier in the week. There in the video was Drake, who was raised Jewish and has alleged that halftime performer Kendrick Lamar insulted his heritage in the same song with which Lamar closed the Super Bowl. There was Jerry Seinfeld, Sasha Baron Cohen and Adam Sandler each with a comedian’s smile looking like they were exacting revenge. It seemed plausible that many in Hollywood had finally had enough and decided to to take a stand. Except they hadn’t.

Why was I fooled? Perhaps it was because I was distracted and using only half my brain. Or, perhaps, it’s because it seemed real and I wanted to believe it. Regardless, I inadvertently spread an AI deepfake created by an Israeli AI entrepreneur without the participation or consent of any of the celebrities in it.

In this case it was anti-hate, but tomorrow it could be anything emotional that triggers an action - to forward the content, to buy or sell a stock, to vote a certain way. What if the celebrities were instead appearing to spread hate or simply seen taking a position on a hot button issue like abortion? That could trigger a boycott and a shift in perceptions by those that only see the deepfakes and never see the rebuttal. What if it was a CEO saying their earnings were going to tank? Or an athlete attacking a friend or a spouse?

Deepfakes spread quickly because they elicit a visceral response and politics, business and culture have become so emotionally charged that we are more wired to respond than ever before. Now think about the effects of all of us being bombarded by such realistic and plausible attempts across every avenue of our personal and professional lives. Even with a low success rate, like with phishing emails, the effects can be really damaging.

We have barely seen the beginning of this story. Buckle up for an unruly ride.

Deepfakes

Deepfakes are increasingly a core business challenge. As I write about in my new book Unruly, the fakes are getting so real, they are costing real businesses real money. Arup, a UK engineering company, found itself out $25 million when one of its clerks in Hong Kong fell victim to a deep fake. The mid-level employee was seemingly asked by the CFO to come to a secretive virtual meeting where they would need to make 15 transactions to five different bank accounts. As gullible as I was proven yesterday, I certainly wouldn’t fall victim to that.

Yet, when the clerk showed up, they were not in a one-on-one call with the CFO but instead on a video call with a group of familiar colleagues who were all there to discuss the urgent need of the CFO. Believing this was actually real, the clerk made the transactions. Yet no one on the call was real. Having never been warned about real-time group deepfakes, at that point the clerk was probably more worried about disobeying than complying. And if no one had warned me or you, we might be easily deceived too.

Artificial Politics

Deepfakes are representative of a new vector of risk that executives must prepare for. I write a lot about Geolegal Risk (the combination of geopolitics and legal risk) as well as LegalAI Risk (when technology meets law), but a central challenge of the next decade will be the third leg of the politics, law and tech triangle. That is Artificial Politics Risk, the vector where politics meets technology.

I wrote about this in a piece last year on deepfakes and the liar’s dividend - or, the phenomenon whereby we see so much fake stuff, we start to think real stuff is fake. The risks continue to build in 2025. Earlier this week, the Canadian Security and Intelligence Threats to Elections Task Force highlighted that more than 30 WeChat accounts spread news stories attacking a would-be Canadian prime minister. A new survey showed that 88% of German voters fear manipulation as they get ready to go the polls later this month and stories of deepfakes swirl. German courts recently found that Elon Musk’s X needs to turn over election misinformation in advance of the German elections in 11 days. French President Macron kicked off an AI summit this by showing deepfake videos that had been generated about him in recent months.

Yet rather than more resources devoted to the challenge, there will be less. The US Attorney General disbanded the FBI’s Foreign Influence Task Force, which was tasked with fighting back against surreptitious election influence efforts by foreign powers like China and Russia. Facebook has gotten rid of fact checkers who effectively served as the platform’s voice on whether something was real or fake. And X has become somewhat of an imperial kingdom where falsehoods are truths if Elon Musk personally deems them to be.

And, yet, deepfakes are just the tip of the Artificial Politics iceberg. Artificial Politics Risk is about how AI will eat democratic capitalism due to job destruction that pulls some countries toward the socialism of Universal Basic Incomes or toward the lure of surveillance and authoritarianism. It is about how technology companies move fast, break things, and make their own rules. It is about war-robots and the use of AI for offensive military - something that came into more focus last week as Google loosened its policies on contributing to AI weapons.

Some days we wake up and it feels like business as usual despite all the shifts in the headlines. I was lulled into that when I passively shared the deepfake, a part of my brain reacted on impulse to something I expected or wanted to be true because there was no obvious label it was false. And, yet, now that I’ve been recently fooled I will be even more suspicious of things that are actually really. That includes the promises of businesses and business leaders, who will need to work even harder in this environment to generate trust and authenticity.

We must do our best not to be deepfaked by real life: Despite occasional calm, the future holds a world of intersectional risks where politics, law and technology present new challenges you need to think about today. I will unpack more on these themes in coming weeklies, as I do in Unruly: Fighting Back when Politics, AI and Law Upend the Rules of Business, which you can pre-order in advance of 25 March.

—SW