GeoLegal Weekly 4- Law and Politics of Supply Chains for Goods, AI and Knowledge by Sean West / Hence Technologies

From supply chain disruptions in the real economy to your AI and knowledge supply chains; plus, lawyers getting spied on, Trump's legal spend, and SCOTUS may overturn major regulatory precedent.

2024 is the year that supply chains become everyone’s problem so today I’ll offer a framework to think about your goods, AI and knowledge supply chains. I’ll also cover blistering hot news from the intersection of geopolitics, law and tech. Welcome, those of you who are joining from Azeem Azhar’s mention of us last week!

Supply chain shocks

The COVID-19 pandemic reminded us that while globalization brought an integrated world economy, supply shocks now ricochet across the globe. For a while, supply pressure came off and it was somewhat back to business as usual. But a triple threat of shocks are bringing supply chain issues - and the legal complications that come with them - back to the fore.

For my interview this week, I’m joined by Dan Currell, a Senior Fellow at the National Security Institute. Dan is an advisor to Hence and a well-known legal industry veteran, who worked with the U.S. National Security Council while he was Deputy Under Secretary of Education. Dan highlights supply chain tension as a top issue he’s watching this year.

As Dan notes, we’ve got supply chain issues brewing in both the Middle East and Asia.

In the Middle East, Houthi rebels in Yemen have been striking supply ships causing a rerouting of freight around Africa. This is adding considerable transportation and insurance cost to products as well as delaying receipt times, which is starting to show up negatively in economic data in Europe. Volvo and Tesla, for instance, are cutting back production because of parts delays in Europe.

At the same time, there are issues shipping through the Panama Canal due to drought. This causes further increased cost and wait times for goods on the other side of the world. Both of these risks are, for now, partially mitigated by a post-pandemic shift to “just in case” inventory stockpiling rather than “just in time” manufacturing, as the World Trade Organization’s head Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala recently pointed out. The question is how long this will hold.

Of course, a bigger risk is that at some point US and Iranian relations sour to the point that Iran closes off the Strait of Hormuz, which would send oil prices skyrocketing as oil equivalent to 21% of the world’s consumption becomes stuck. This is less farfetched than it was a few weeks ago, before the US blamed an Iran-backed group for a drone strike that killed US soldiers in Jordan and before the US retaliated with strikes in Syria and Iraq.

But there’s a second dynamic at play. Acute stoppages like those in the Red Sea, Panama Canal or even Strait of Hormuz are headaches but are unrelated to the trading partners themselves. That is to say that once there is more rain in Panama, or once the Houthis are deterred or defeated, the stoppage will abate. So these shocks are really about preparation and resilience.

This is very different from the reordering of supply chains that we have seen and will see in coming months and years. While there has been a lot of talk and effort related to “onshoring,” “nearshoring” and “friendshoring”, the reality is that major economies are still very exposed to trading relationships with geopolitical rivals - or at least countries which are unaligned, which implies further reordering for today’s treacherous world. This comes on the back of an uptick in sanctions and trade restrictions “from about 650 new restrictions in 2017 to more than 3,000 in 2023.”

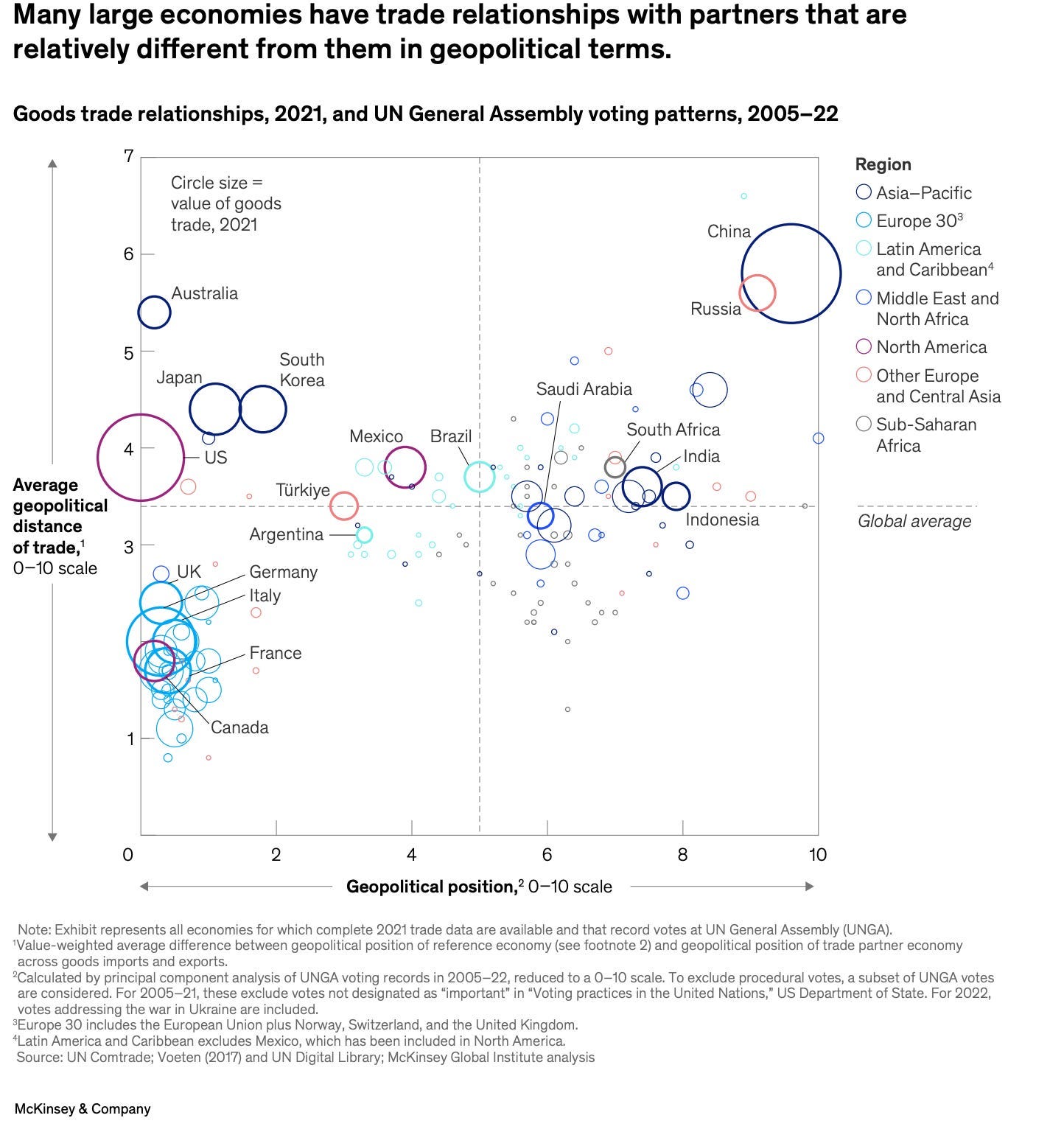

McKinsey just released a fascinating study that measures the “geopolitical distance” of trading relationships while showing the size of the economies affected (see image below). I see it as an assessment of how likely supply chains are to be disrupted by geopolitical rivalry, as measured by whether countries vote together at the UN General Assembly. In the chart below, the Y-axis shows whether countries are more or less likely to be trading with friends - so the higher a country is on the chart, the more it trades with geopolitical rivals. If we assume that trading with rivals creates geopolitical risk these days, among the most exposed economies are China, Russia, and Australia (the latter due to trade with China). Japan and South Korea have moderate exposure, again largely due to their high volume of trade with China. The US has average exposure to unaligned trading partners, and Europe is (now) mostly trading amongst friends.

The upshot to me is that there is likely to be more volatility in trade reorganization in the medium-run than we might have thought - and it affects some of the world’s biggest economies, as the big circles below show. This means that everyone will be impacted directly or indirectly as politics becomes more volatile. Beyond hot wars, the 70 elections in 2024 feature a number of nationalists who are acutely aware of the impact of globalization on jobs at home while regionalism is feeling like a more compelling framework for many countries than globalization.

Which brings us to supply chain risk out of Asia. First, as US-China rivalry has ticked up, and as the operating climate in China has gotten more challenging for foreign firms, countries are diversifying their supply chains. India and Vietnam have been winners to date. Second, Western countries are offering incentives to bring jobs back onshore, which shifts the calculus and encourages supply chain shifts. Third, there’s a non-zero risk that China begins to step up pressure on Taiwan over the course of 2024 which could ultimately put the semiconductor supply chain at risk, not to mention the broader trading relationship.

So what should companies do? The crux of all of this is to have a framework for all of the choices one must make in weighing up increased supply chain risk against everything required to shift the supply chain. There are a host of economic variables that are well covered elsewhere but my focus is on the legal concerns.

Reordering supply chains is fraught with legal risk and is a complicated calculation - it is something GCs are being asked about more often at Board level. I am interested in mapping out the legal vector of how politics impacts companies, so I’m constantly looking for decent law firm frameworks in response to political issues. Freshfields put together a guide to supply chain legal issues from the pandemic, which I think captures the core elements that must be considered. For instance:

Can you claim a basis for renegotiating a long term contract due to force majeure or material adverse change?

Is exiting a supplier relationship viable, particularly when that involves lengthy consultation processes, employment litigation risk, exit taxation, IP allocation and the like?

Will new suppliers be reliable and also be able to guarantee compliance with human rights, ESG, corruption and other requirements?

Do you have have expertise and the right foreign counsel partners to navigate related foreign legal issues (more on that below)?

Such assessments are not easy but will be front of mind for businesses, particularly if 2024 elections deliver nationalists who favor increased tariffs that make certain trading relationships too expensive to maintain. No doubt law firms that offer related assessments will be increasingly in demand.

AI Supply Chains

As hard good supply chains get tougher to manage, it’s important to also consider your knowledge supply chain. Last week I covered AI regulation in depth, and AI is a particularly interesting aspect of the knowledge supply chain. This is because it is effectively a hybrid good - while the product of AI is knowledge (“chat” outputs, algorithmic recommendations etc) it’s production is hugely dependent on physical inputs.

That is to say that as companies become more and more dependent on AI outputs, they also depend on the ability of AI providers to scale and reliably provide service. Key to that is the continued development of the compute and data centers to manage it, which comes with a number of risks. First, there is competition between US and China to keep their AI supply chains separate - and that goes all the way down to accessing chips that make AI possible. Second, there is environmental impact (data centers already account for 1% of global emissions) and the potential exposure to the politics of where those centers are placed as they scale to power the global economy with AI.

But there are a lot of other countries competing - for instance, Iran’s Supreme Leader says it wants to be in the top 10 AI countries. And there are a host of other factors that determine the geography of AI - like where data is produced, how it can be accessed, and how both capital and innovation create the ability for countries to advance. If you want to know more about it, you should read this excellent Harvard Business Review piece which ranks AI nations - but suffice it to say that the AI supply chain is as exposed to politics as the hard goods supply chain.

Legal Knowledge Supply Chain

Having walked through supply chain shocks in both hard goods and AI, we can now finish our analysis with some thinking about your legal knowledge supply chain as a company.

Knowledge is created within a company in many ways. It can be built through research and development. It can be purchased through an acquisition of a competitor. It can be co-created with a partner firm.

But perhaps the most common way that new knowledge enters a company is via outsourcing. That work usually connotes the offloading of lower-value tasks that can be done more cost-effectively offshore. Yet, increasingly higher value knowledge tasks are assigned to external partners.

While we don’t often think of it this way, retaining a law firm to advise on granular issues related to, say, a merger is a decision to outsource - and leverage that firm’s knowledge instead of building it internally. While I’m focusing here on law, the same is true for offloading other knowledge intensive tasks done by management consultants and the like.

This type of reliance on external expertise seems to have increased since the pandemic. Once employees went hybrid or global, the seamless integration of external actors - and even fractional executives - into digital teams became easier. As organizations have become nimbler, more specialized and more agile for the future, they need more specialist knowledge to be successful so they outsource more.

Taking a supply chain view of knowledge can help manage legal risk. As the world becomes more uncertain, it is important to ask the following questions:

How is expertise entering my legal department and my company? For instance, do I rely mostly on employees I hire, external counsel or even generative AI solutions?

With respect to internally generated knowledge:

When I am hiring and growing talent, does this stem from a strategy related to our knowledge gaps? For example, is my organization proactive in recruiting for the expertise needed to comply with AI regulations in the future?

What expertise do I have in-house that I will call upon if particular risks manifest? For instance, am I in a position to move swiftly to renegotiate hard good supply contracts without being dependent on a third party?

Do we have this knowledge internally already and I just can’t source it? This would happen if you have lots of smart people in a large law department but only a clear sense of their current job functions, not the collective knowledge and experience they bring from past roles or jobs.

Do I have people who can ask the right questions, manage external experts and integrate insights into our legal strategy or legal operations?

With respect to externally generated knowledge:

Where I do bring in external knowledge, am I confident that I have selected my advisors based on being the best - not based on inertia? For instance, if my long-standing partner law firm tells me they can help me on something new like cryptocurrency in Central Asia, do I give them the work out of habit or can I confirm they are truly the best resource?

Do I have a critical dependency on an organization that may be exposed to its own political, economic or legal risks - for instance, by virtue of being in a challenging geography or representing controversial clients?

With respect to technology generated knowledge:

What role does AI powered software play in my knowledge supply chain today?

Do I have controls to make sure that to the extent my staff are using generative tools, we are not incorporating hallucinations as if they are truths into documents and knowledge that will be drawn upon again in the future?

How are we dealing with knowledge leakage that is bound to occur with AI tools in the supply chain?

One way to address the risks in your knowledge supply chain is to take the same approach you would in a hard goods supply chain. That is to say:

Diversify your sources of input to get a fuller view

Create alternatives to knowledge “chokepoints” - can you metaphorically go around the Horn of Africa if the Red Sea presents issues?

Create negotiating leverage to ensure that your providers are giving you their best resources - don’t settle for second-run product

In Other News

Spying on Lawyers - I wrote a piece at the onset of the Russia - Ukraine war about how lawyers, long treated similar to diplomats on the sidelines of global spats, were becoming the targets of sanctions. Now, they are getting spied on using the nuclear weapon of spying - Pegasus software, which is spyware that can be surreptitiously installed on phones without detection and can monitor all communications. Early this week, it was reported that a prominent human rights lawyer in Jordan was targeted by Pegasus spying software in 2021 and 2022. Past reports of lawyers being targeted include in Bahrain, Hungary, India, Poland, Spain, and UAE. To the extent that this is being done by governments or opposition groups to send a chill through the use of the legal system, it aligns with our 2024 Outlook theme of Rule of Law Recession.

Trump’s Lawyer Stimulus - While Trump’s $88 million fine grabbed headlines, his $76 million legal bill over the last two years has been less prominent. A number of Trump’s lawyers have been paid over $5 million each by his campaign including $6 million to the lawyer that lost him $88 million. Anyone have a good spend management solution to sell him?

Big SCOTUS Regulation Case - In short, courts must to defer to federal agency interpretations of ambiguous law in the US so long as they are reasonable due to a precedent called Chevron. This may be overturned. There would a lot of implications for how new laws and regulations are interpreted, including for future AI regulation - if it gets overturned, I’ll cover it further.

—

I get the privilege of writing GeoLegal Notes but the ideas here reflect the work of others including Dan Currell, whose inputs go beyond just the interview; my co-founder Steve Heitkamp, who helped develop the AI and knowledge supply chain perspectives; and Mia Tellmann for scouring the world for interesting content.

-SW

Very good article, Sean. Can I translate part of this article into Spanish, with links to you, and a description of your newsletter and you?

Sean, good work as always. One entry in your section on knowledge supply chains caught my eye:

<<Do I have a critical dependency on an organization that may be exposed to its own political, economic or legal risks - for instance, by virtue of being in a challenging geography or representing controversial clients?>>

That opens up the intriguing line of thought regarding the extent to which a company's outside law firm itself constitutes a risk to the company. I can think of a few examples:

- Most obviously, the firm is relatively lackadaisical in its cyber-security, and either confidential client data is stolen or malware infiltrates the company through an outside lawyer's email account.

- The firm is unexpectedly consumed in a merger or collapses altogether, causing great disruption to the continuity of client business and confusion about the status of critical files.

- Relatedly, the firm conducts so much client business that it becomes "too big to fail" from the company's perspective and the company finds itself considering the equivalent of a bailout package.

- As you note, the firm is embroiled in controversy because of a client it represents (Trump and Israel are obvious current examples, but more will emerge) and the client suffers collateral reputational damage.

- To your point about geography: Is the firm HQ'ed in a coastal city where climate-change risks are much higher? Look at what happened in LA this past week, or what SuperStorm Sandy did to New York.

I'm pretty sure that no large law firms, when scanning the horizon for risks to their biggest clients, ever turn the binoculars on themselves. But maybe they should start.